MALAYSIAN DENTAL JOURNAL · Dr. Yap Yoke Yong Dr. Sharifah Tahirah Al-Junid Dr. Nurshaline Pauline...

Transcript of MALAYSIAN DENTAL JOURNAL · Dr. Yap Yoke Yong Dr. Sharifah Tahirah Al-Junid Dr. Nurshaline Pauline...

Editor: Associate Professor Dr. Ngeow Wei CheongBDS (Mal), FFDRCSIre (Oral Surgery), FDSRCS (Eng), AM (Mal)Department of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery,Faculty of Dentistry, University of Malaya,50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.E-mail: [email protected]

Assistant Editor: Dr. Haizal Mohd HussainiDr. Chai Wen Lin

Secretary: Dr. Zamros YuzadiTreasurer: Dr. Lee Soon BoonEx-Officio: Dr. Wong Foot Meow

Editorial Advisory Board:We wish to express our sincere thanks to all members of the Editorial Advisory Board who gave their time willingly toreview article as well as to assist with the editorial work of this journal.

Dr. Elise Monerasinghe Professor Dr. Michael Ong Professor Dr. Phrabhakaran NambiarDr. Seow Liang Lin Dr. Lam Jac Meng Dr. Roslan SaubDr. Nor Adinar Baharuddin Assoc. Prof. Dr. Nor Zakiah Mohd Zam Zam

The Editor of the Malaysian Dental Association wishes to acknowledge the tireless efforts of the following referees toensure that the manuscripts submitted are up to standard.

Dato’ Dr. Chin Chien Tet Prof. Dr. Ong Siew Tin Prof. Dato’ Dr. Ishak Abdul RazakProf. Dr. Toh Chooi Gait Dr. Roslan Abdul Rahman Prof. Dr. Ghazali Mat Nor Prof. Dr. Michael Ong Dr. Lam Jac Meng Prof. Dr. Rahimah Abdul Kadir Dr. Haizal Hussaini Dr. Elise Monerasinghe Prof. Dr. Tara Bai Taiyeb AliDr. How Kim Chuan Dr. Sadna Rajan Prof. Dr. Phrabhakaran NambiarDr. Ismadi Ishak Dr. Ajeet Singh Prof. Dr. Nasruddin JaafarDr. Shahida Said Dr. Roslan Saub Prof. Dr. Nik Noriah Nik HusseinDr. Roszalina Ramli Dr. Norliza Ibrahim Prof. Dr. Zainal Ariff Abdul RahmanDr. Norintan Ab. Murat Pn. Rathiyah Ahmad Prof. Dr. Dasan SwaminathanDr. Ros Anita Omar Dr. Siti Mazlipah Ismail Prof. Dr. Rosnah Mohd ZainDr. Zamros Yuzadi Dr. Chai Wen Lin Assoc. Prof. Dr. Datin Rashidah EsaDr. Siti Adibah Othman Dr. Wong Mei Ling Assoc. Prof. Dr. Raja Latifah Raja JallaludinDr. Reginald Sta Maria Dr. Dalia Abdullah Assoc. Prof. Dr. Khoo Suan PhaikDr. Seow Liang Lin Dr. Chew Hooi Pin Assoc. Prof. Dr. Tuti Ningseh Mohd DomDr. Noriah Hj. Yusoff Dr. Lew Chee Kong Dr. Nor Adinar BaharuddinDr. Yap Yoke Yong Dr. Sharifah Tahirah Al-Junid Dr. Nurshaline Pauline Hj KipliDr. Nor Azwa Hashim Dr. Wey Mang Chek Dr. Zeti Adura Che Abd. Aziz

1

MALAYSIAN DENTAL JOURNAL

Malaysian Dental Journal (2006) 27(1) 1-2© 2006 The Malaysian Dental Association

Malaysian Dental Association Council 2006-2007President: Dr. Wong Foot MeowPresident-elect: Dato’ Dr. Low TeongImmediate Past President: Dr. Shubon Sinha Roy Hon. General Secretary: Dr. How Kim ChuanAsst. Hon. Gen. Secretary: Dr. Abu Razali bin SainiHon. Financial Secretary: Dr. Lee Soon BoonAsst. Hon. Finan Secretary: Dr. Sivanesan SivalingamHon. Publication Secretary: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ngeow Wei Cheong Chairman, Northern Zone: Dr. Koh Chou HuatSecretary, Northern Zone: Dr. Neoh Gim BokChairman, Southern Zone: Dr. Steven Phun Tzy ChiehSecretary, Southern Zone: Dr. Leong Chee SanElected Council Member: Dr. Sorayah SidekElected Council Member: Dr. Chia Ah ChikNominated Council Member: Dr. V. NedunchelianNominated Council Member: Dr. Xavier Jayakumar Nominated Council Member: Dr. Hj. Marusah Jamaludin Nominated Council Member: Dr. Lim Chiew Wooi

The PublisherThe Malaysian Dental Association is the official Publication of the Malaysian Dental Association. Please address all correspondence to:

Editor,Malaysian Dental Journal

Malaysian Dental Association54-2, (2nd Floor), Medan Setia 2,

Plaza Damansara, Bukit Damansara,50490 Kuala Lumpur

Tel: 603-20951532, 20947606, Fax: 603-20944670Website address: http://mda.org.my

E-mail: [email protected]@streamyx.com

2

Aim And ScopeThe Malaysian Dental Journal covers all aspects of work in Dentistry and supporting aspects of Medicine. Interactionwith other disciplines is encouraged. The contents of the journal will include invited editorials, original scientificarticles, case reports, technical innovations. A section on back to the basics which will contain articles covering basicsciences, book reviews, product review from time to time, letter to the editors and calendar of events. The mission is topromote and elevate the quality of patient care and to promote the advancement of practice, education and scientificresearch in Malaysia.

PublicationThe Malaysian Dental Journal is an official publication of the Malaysian Dental Association and is published half yearly (KDN PP4069/12/98)

SubscriptionMembers are reminded that if their subscription are out of date, then unfortunately the journal cannot be supplied. Sendnotice of change of address to the publishers and allow at least 6 - 8 weeks for the new address to take effect. Kindly usethe change of address form provided and include both old and new address. Subscription rate: Ringgit Malaysia 60/- foreach issue, postage included. Payment in the form of Crossed Cheques, Bank drafts / Postal orders, payable to MalaysianDental Association. For further information please contact :

The Publication SecretaryMalaysian Dental Association

54-2, (2nd Floor), Medan Setia 2, Plaza Damansara, Bukit Damansara,50490 Kuala Lumpur

Back issuesBack issues of the journal can be obtained by putting in a written request and by paying the appropriate fee. Kindly sendRinggit Malaysia 50/- for each issue, postage included. Payment in the form of Crossed Cheques, Bank drafts / Postalorders, payable to Malaysian Dental Association. For further information please contact:

The Publication SecretaryMalaysian Dental Association

54-2, (2nd Floor), Medan Setia 2, Plaza Damansara, Bukit Damansara,50490 Kuala Lumpur

Copyright© 2006 The Malaysian Dental Association. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored ina retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by means of electronic, mechanical photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the editor.

Membership and change of addressAll matters relating to the membership of the Malaysian Dental Association including application for new membershipand notification for change of address to and queries regarding subscription to the Association should be sent to HonGeneral Secretary, Malaysian Dental Association, 54-2 (2nd Floor) Medan Setia 2, Plaza Damansara, Bukit Damansara,50490 Kuala Lumpur. Tel: 603-20951532, 20951495, 20947606, Fax: 603-20944670, Website Address:http://www.mda.org.my. Email: [email protected] or [email protected]

DisclaimerStatements and opinions expressed in the articles and communications herein are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the editor(s), publishers or the Malaysian Dental Association. The editor(s), publisher and the MalaysianDental Association disclaim any responsibility or liability for such material and do not guarantee, warrant or endorse anyproduct or service advertised in this publication nor do they guarantee any claim made by the manufacturer of such productor service.

3

MALAYSIAN DENTAL JOURNAL

Malaysian Dental Journal (2006) 27(1) 3© 2006 The Malaysian Dental Association

4

MALAYSIAN DENTAL JOURNAL

CONTENT

Editorial : Selling Our Content to the International Community 5

Malaysian Private Dental Practitioners in Continuing Professional EducationRazali AS, Rozima Y, Shamsuddin A 6

Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma – Relevant Laboratory DiagnosisSolomon MC, Rao NN, Carnelio S 14

Amelogenesis Imperfecta with Gingival Hyperplasia and Anterior Open Bite – A Case ReportMadhu S 20

Orthodontics and Restorative Management of Hypodontia in an Adult: A Case PresentationHow KC 24

Non-extraction Orthodontic Treatment in Management of Moderately Crowded Class II Division 2 Malocclusion: A Case ReportOthman SA 30

Randomised Clinical Trial: Comparing the Efficacy of Vacuum-formed and Hawley Retainers in Retaining corrected tooth rotationsRohaya MAW, Shahrul Hisham ZA, Doubleday B 38

Dental Students’ Reflections: A Study of Video-triggered Reflections in Dentist-patientCommunication Skill ClassMurat NA 45

The Expert Says…Raja Latifah RJ, Saub R 49

Malaysian Dentists’ Opinion on Fixed Prosthodontics Teaching during Undergraduate TrainingTandjung YRM, Morad SM, Zakaria N, Ibrahim N 52

Instructions to contributors 60

Malaysian Dental Journal (2006) 27(1) 4© 2006 The Malaysian Dental Association

Cover page : Photomicrographs showing various states and cellular appearances of oral squamous cell carcinoma using Periodic Acid Schiff stain (10X magnification), Silver stain (40X magnification) andImmunohistochemical stain (40X magnification). Picture courtesy of Professor Dr. Monica Solomon.

5

MALAYSIAN DENTAL JOURNAL

In the second issue of the 2005 Malaysian Dental Journal editorial. I have promised to look into the possibility ofindexing the Malaysian Dental Journal

Well, in a way, we are getting back to the world community, though not directly via indexing, but throughpartnership in selling our content. And for all this to happen, I must first thank YBhg Professor Dato’ Dr. IshakAbdul Razak, an active member of the Malaysian DentalAssociation (MDA) who first set up a communication forme with Ms Heather Rahhal of the EBSCO Publishing. Weare now in the midst of signing a contract with this publishing company, who will under take to sell the content of the Malaysian Dental Journal. Let me tell you alittle bit more about our partner.

Established in 1984, and headquartered in Ipswich,Massachusetts, EBSCO Publishing (EP) is a subsidiary ofEBSCO Industries. EBSCO Publishing is chartered with delivering full-text and bibliographic research databases to the school, public, academic, medical, corporate and government library marketplace.

EBSCO Publishing currently licenses the full text contentof over 8,000 well-known periodicals and databases. They license content from thousands of well-known publications including: Fortune, National Geographic,Newsweek, the New Yorker, the Washington Post, Time,Atlantic Monthly, the Harvard Business Review, BusinessWeek, U.S. News & World Report, Vanity Fair, andConsumer Reports. Of course, it would be nice for theMalaysian Dental Journal to eventually rank similar tothese high impact publications.

The primary benefit for the Malaysian Dental Associationfor working with EBSCO Publishing is the greatlyincreased American and international exposure. Theirresearch database products are installed in close to 90% of

the public and academic libraries in the United States andCanada. EP also has excellent penetration in WesternEurope, and, due to an exclusive arrangement with a philanthropic organisation, their products are installed inevery college, university and public library in the following countries: Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan,Bangladesh, Belarus, Bosnia Herzegovina, Bostwana,Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, Georgia,Ghana, Guatemala, Haiti, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Latvia,Lithuania, Macedonia, Malawi, Moldova, Mongolia,Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Poland, Russia, Serbia,Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Sweden,Tanzania, Uganda, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Zambia,Zimbabwe. In Asia-Pacific, EBSCO Publishing has anactive sales force, with strong and growing product penetration in the libraries of Australia, New Zealand,Japan, China, Hong Kong, S. Korea, Taiwan, and thePhilippines. This means the Malaysian Dental Journal willbe made available to all these corners of the world.

The Malaysian Dental Association signed a standard, non-exclusive agreement that will not prevent it in any wayfrom working with other companies like EP, nor from distributing full-text via the Web or other electronic channels. Hence, members will still be able to access to theMalaysian Dental Journal when it is eventually uploadedto the MDA webpage.

Thank you.

Associate Professor Dr. Ngeow Wei CheongEditorMalaysian Dental Journal

Malaysian Dental Journal (2006) 27(1) 5© 2006 The Malaysian Dental Association

Editorial : Selling Our Content to the International Community

6

Malaysian Private Dental Practitioners in Continuing Professional EducationContextRazali AS BDS Malaysian Private Dental Practitioners’ Association, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Rozima Y MSc. Malaysian Private Dental Practitioners’ Association, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Shamsuddin A BSc., Ed.D. Malaysian Private Dental Practitioners’ Association, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

ABSTRACTThis cross-sectional survey research was done to identify the current scenario of participation in Continuing ProfessionalEducation (CPE) among private dental practitioners in Malaysia. The findings serve as empirical evidence and the foundationof framework for mandatory CPE proposed by Ministry of Health Malaysia. A cross-sectional survey research was conducted. A systematic random sampling technique was used to select every 5th individuals from the 1,426 private dentalpractitioners (N) listed in the Malaysian Dental Council register, to give a total of 313 sample individuals (n). Survey questionnaires were mailed to the sample individuals and 233 questionnaires were collected, giving a response rate of 74 percent. The findings implied that private dental practitioners who join higher number of professional associations, whoread/comment/write higher number of journals, and who earn higher income, participate in higher number of CPE. Privatedental practitioners showed highest preference to learning from experience and from peers. The utmost important factor ofparticipation in CPE was suitability of courses to practice. However, the level of participation in CPE was found to be farbelow the expectation, the level of attitude towards CPE was low, and the level of self-esteem among private dental practitioners in Malaysia was of serious handicap. Significant relationships were established between attitude towards CPEand participation in CPE, between participation in CPE and self-esteem, and between attitude towards CPE and self-esteem.

Key words:continuing professional education, private dental practitioners, participation, attitude, self-esteem

INTRODUCTION

Malaysian Private Dental Practitioners’Association(MPDPA) has been actively organising ContinuingProfessional Education (CPE) programs for its membersand non-members in collaboration with independentproviders such as dental suppliers, but the number of members who actively involved in CPE programs is relatively small, be it in organising or participating. As of December 2003, there are 1,426 private dental practitioners and 992 public dental practitioners inMalaysia (a total of 2,418 dentists), giving dentists to population ratio as 1:10,612.1 As of July 2004, there areonly 411 active members in MPDPA, which constituteonly 29 percent of the private dental practitioners inMalaysia. Many private dental practitioners remain passiveand do not involve and participate in many of the CPE programs organised by the association, with an averagenumber of 100 participants per CPE program (Source:MPDPA).

This has created apprehension among some privatedental practitioners that each of these non-participativepeers would lag behind in the development of the latest

jargon in technology, skills, opportunities and knowledge,also challenges in the new era of globalisation, and facedifficulties to cater to the needs of 10,612 people in dentalcare. Thus MPDPA is firm with its stand to spearheadefforts to implement mandatory CPE for dental practitioners and to give its full support to the Ministry ofHealth (MOH) Malaysia for its implementation.

At the time this research was conducted, CPE amonghealthcare professionals were left to individuals’ prioritiesand conscience, and voluntary. There was no objective measurement, or yardstick that could be used for appraisal,recertification, or promotional prospects. Hence, the lowlevel of participation in CPE among private dental practitioners is associated with the voluntary basis of participation, thus there is no strong need for them to engageor participate in CPE and the importance of CPE is not givenpriority. But with the proposal by the MOH to implementmandatory CPE for recertification of Annual PracticeCertificate (APC) on healthcare professional, dental practitioners must accept the notion that the MOH has recognised CPE as the tool to equip them with certain competency required in their practice. Through active participation in CPE programs, private dental practitioners

Malaysian Dental Journal (2006) 27(1) 6-13© 2006 The Malaysian Dental Association

MALAYSIAN DENTAL JOURNAL

7

Razali / Rozima / Shamsuddin

are exposed to a new ASK (attitude, skills, knowledge) level.Dental practitioners don’t get to grow alone if they are confined to their professional practices and busy makingmoney on whatever basic skills they have. They couldbecome deprived of professional updates on the newer concepts, advance techniques and latest armamentarium.They must seek whatever available means to improve theirskills and knowledge, and act in the right attitude to add values in their practices and to secure success in their profession.

Increase in ASK level is often associated withimproved self-esteem.2 Baumeister et al.3 concluded that inperformance context, high self-esteem people appear touse better self-regulating strategies than low self-esteempeople and there are positive correlations between job performance and self-esteem. Orpen4 indicated that thosewho received more formal training received superior ratings of improved job performance and that those withmore formal training had greater confidence in their ability to do their jobs. Daley5 indicated that professionalsreported CPE as a tool to help them reaffirm their knowledge; contributes to their personal growth andincreases their confidence. Knowledge learned in CPEbecomes meaningful through processes they use to linkinformation with their practice and that meaning is directly to the nature of professional work in which theyengage.

However, attendance at CPE programs is still relatively small. In order to increase participation in CPE,thus increasing the status of dental profession and improving the standard of dental health care in Malaysia,MPDPA aspires to assist the MOH in constructing theframework of mandatory CPE by providing empirical evidence of the current scenario of participation in CPEamong private dental practitioners.

OBJECTIVES

The general objective of this study is to identify thecurrent scenario of participation in CPE among privatedental practitioners in Malaysia, and its relationships withattitude towards CPE and self-esteem, and to use it as thefoundation for the mandatory CPE point system framework. The specific objectives are:(1) to determine the level of participation in CPE, the level

of attitude towards CPE and the level of self-esteemamong the respondents;

(2) to determine the relationships of level of participationin CPE, the level of attitude towards CPE and the levelof self-esteem among the respondents with selectedvariables in demographic factors;

(3) to determine the relationships between participation inCPE and attitude towards CPE, between participationin CPE and self-esteem, and between attitude towardsCPE and self-esteem; and

(4) to determine factors that contribute to the participationin formal CPE among the respondents.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

Population and Sampling

The target population for this study is the privatedental practitioners in Malaysia who are currently registered to the Malaysian Dental Council (MDC). As atDecember 2003, the population size was 1,426 (N). A systematic sampling was used, where every 5th individualsfrom the register of dental practitioners in Malaysia wereselected, regardless of the state in which they practice, andgender. Hence, a total of 313 sample individuals wereselected from the population of private dental practitionersin Malaysia.

A structured self-administered mailed survey questionnaire was developed and was use as an instrumentfor data collection. Descriptive measures such as mean,minimum, maximum, and percentages were used todescribe the variables in demographic attributes and learning preference in non-formal CPE. Comparisonanalysis (t-test and ANOVA) was carried out to determinethe differences in participation in CPE, attitudes towardsCPE and self-esteem between and among variables indemographic attributes and learning preference.Correlation analysis of Pearson Product Moment was usedto determine the relationships between participation inCPE and self-esteem, and 8 other relationships betweenselected variables.

RESULT

Of the 313 sample individuals selected in thisresearch, 233 individuals responded to the questionnaire,which gives the value of response percentage 74 percent.

Most of the respondents were aged between 31 to40 years old, which consist of about 37 percent of the total.Majority of the respondents (39 percent) have been practicing for 11 to 20 years. About 81 percent of therespondents were private dental practitioners who havetheir own practice. In terms of monthly earned income,about 25 percent of the respondents earn medium income(RM6001 to RM9000) and 23 percent of them earn veryhigh income of more than RM15000 per month. Therespondents were evenly distributed in terms of graduationorigin i.e. from local universities and overseas. However,about 88 percent of the respondents were general dentalpractitioners and the rest were specialists. Majority of therespondents (about 89%) belonged to at least one professional association, whereas the other 11 percent didnot belong to any professional association at all. About 42percent of the respondents did not subscribe to any professional journal and the rest subscribed to at least oneprofessional journal. In terms of total number of journalsread/commented/written in the past year, about 20 percentof the respondents did not engage in any of these activities.On the average, the respondents read/commented/wroteabout only 3 journals per year. In terms of learning preference in non-formal CPE, the respondents showed

8

Malaysian Private Dental Practitioners in Continuing Professional Education Context

highest preference to learning from experience and lowestpreference to transformational learning. The 2 most significant factors of participation in formal CPE weresuitability of courses to the respondents’ practice and personal and professional development, whereas the 2least significant factors were accreditation of CPE pointsand certificate of attendance.

A total of 93 percent of the respondents did notmeet the expectation to acquire minimum CPE credithours within a year, with about 19 percent of them did notparticipate at all in any CPE program. About 31 percent ofrespondents between the ages of 21 to 30 years old, andzero percent of those who were more than 71 years oldnever participated in any CPE. Detail analysis of distribution of participation in formal CPE found thatrespondents who met and exceeded the minimum requirement of CPE hours in a year are between the agesof 31 to 70 years old (a total of 7%), have been practicingfor 6 to 30 years (a total of 7%), who have their own practice (a total of 7%), reported medium to very highincome (a total of 7%), graduated from overseas (5%), aregeneral practitioners (6%), belonged to more than one professional association (7%), subscribed to more than oneprofessional journal (5%), and read/commented/wrotemore 1 to 3 journals a year (6%). The rest of the respondents do not meet the minimum requirement of CPEhours in a year. However, further comparison analysisfound that there was no difference in participation in formal CPE between and among groups in types ofemployment, graduation origin, level of qualification, agecategories, and period of practice, but there were significant difference in participation in formal CPEamong the groups in income categories (higher participation among dental practitioners who earn higherincome), among the groups in enrollment to professionalassociation categories (higher participation among practitioners who enroll in higher number of professionalassociations) and among the groups in number of journalsread/commented/write (higher participation among practitioners who read/comment/write more journals).

Majority of the respondents had low attitudetowards CPE (84%). On the average, the respondents werefound to have low attitude towards CPE. However, most of

the respondents honor people who continuously learnthroughout life and were open to learning from their peers.Further comparison found that there were significant difference in attitude towards CPE between and amonggroups in level of qualification (higher attitude towardsCPE among specialist compared to general practitioner),age categories (higher attitude towards CPE amongyounger respondents compared to older ones), period ofpractice (higher attitude towards CPE among respondentswho had shorter period of practice compared to those oflonger ones), and participation categories (higher attitudetowards CPE among respondents who participated in higher number of CPE compared to those of lower ones).On the average, the respondents were of serious handicapof self-esteem. Only a total of 17 percent of the respondents had good self-esteem (9%) and sound self-esteem (8%). Majority of the respondents were mostagreed that when they complete a task, large and small,they feel proud of their accomplishment, but they weremost disagreed that they are not hurt by other’s opinions orattitudes. Further comparison found that there were significant difference in self-esteem between and amonggroups in graduation origin (higher self-esteem amongspecialists compared to general practitioners), age categories (higher self-esteem among respondents whowere older compared to those who were younger), periodof practice (higher self-esteem among respondents whohad longer period of practice compared to those of shorterones), participation categories (higher self-esteem amongrespondents who participated in higher number of CPEcompared to those of lower ones), and attitude categories(higher self-esteem among respondents who had higherattitude towards CPE compared to those of lower ones).

Further analysis found that there were significantrelationships between participation in CPE and self-esteem, attitude towards CPE and self-esteem, age andself-esteem, period of practice and self-esteem, betweenparticipation in CPE and attitude towards CPE, andbetween attitude towards CPE and period of practice. Nosignificant relationships were established between participation in CPE and age, participation in CPE andperiod of practice, and attitude towards CPE and period ofpractice (Table 1).

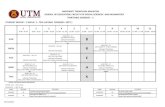

Table 1: Summary of correlational analysis between selected variables

Dependent Variables Independent Variables Pearson Correlation, r Sig-r Significant Relationship

Self-esteem Participation 0.188 0.004 YesSelf-esteem Attitude 0.361 0.000 YesSelf-esteem Age 0.288 0.000 YesSelf-esteem Period of Practice 0.325 0.000 YesParticipation Attitude 0.247 0.000 YesParticipation Age -0.037 0.570 NoParticipation Period of Practice -0.023 0.725 NoAttitude Age 0.099 0.133 NoAttitude Period of Practice 0.131 0.045 Yes

Significant level, _ = 0.05

9

Razali / Rozima / Shamsuddin

DISCUSSION

There are 1,426 private dental practitioners and 992public dental practitioners in Malaysia (a total of 2,418dentists), giving dentists to population ratio as 1:10,612.1

The samples in this study were systematically selected inrandom, thus it can be generalised to the whole populationof private dental practitioners in Malaysia.6 Alreck &Settle7 stated that it was seldom necessary to sample morethan 10 percent of the population. They disputed the logic that sample size was necessarily dependant upon population size. However, choice of sample size is often asmuch a budgetary consideration as a statistical one, and bybudget it is useful to think of all resources (time, space andenergy) not just money.7 Generally choice of sample size isas much a function of budgetary considerations as it is statistical considerations. When they can be afforded, largesamples are usually preferred over smaller ones. Based onthese reasons, a sample size of 313 (n) was selected fromthis population, consistent with recommendations fordetermining size of a random sample.8

The original population register was in randomorder, thus systematic sampling would yield a sample thatcould be statistically considered a reasonable substitute fora random sample.9 Randomisation is used to eliminatebias, both conscious and unconscious, that the researchermight introduce while selecting a sample. Kerlinger6

described randomisation as the assignment of objects (subjects, treatments, groups, etc.) of a population to subsets (sample) of the population in such a way that forany given assignment to a subset (sample), every memberof the population has an equal probability of being chosen.Randomization is essential for probability samples whichare the only samples that can generalise results back to thepopulation. Gay10 reported that random sampling was thebest single way to obtain a representative sample. No technique, not even random sampling, could guarantee arepresentative sample, but the probability is higher for thisprocedure than for any other.

Any deficiency or lack of professional competencyin a single dental practitioner would affect 10,612 people.Thus, it is very imperative to ensure dentals practitionersare soundly equipped with relevant competencies in theirpractice, and have high confidence in carrying out theirduties as caregivers. The smaller number of specialists ascompared to general practitioners among private dentalpractitioners shows that there is a serious lack of participation in CPE or further education. Private dentalpractitioners need to be made aware of the importance ofspecialisation in their profession in relation with their ethical obligation to serve the community. They should beaware that if they do not engage in further education orCPE, each of them will be responsible in failing to meetthe increasing demand and fulfilling growing needs in thewellbeing of 10,612 people in dental care. The followingsare the discussion on some of our finding:

Finding #1: Age, period of practice, graduation origin,level of qualification and type of employment do notcontribute to participation in CPE. However, privatedental practitioners who earn lower level of incomehave constraint to participate in CPE, and they avoidpossible loss of income.

When linking participation in CPE with demographic attributes, it is observed that the participationlevel in CPE is of no significant difference between practitioners who have their own practice and those who are employed, between specialists and general practitioner, between practitioners who graduated fromlocal universities and overseas, between younger and olderpractitioners, and between those who have more experience in this profession and those of less. This contradicts the findings in earlier research by Buck &Newton11 who found that dental practitioners who havebeen qualified for between 21 and 30 years, and those whohave gained additional qualifications after qualifying as adentist, participate more in CPE. They continued to pointout that attendance at postgraduate dental courses is related to possessing additional qualification, and notbeing a general practitioner. It also contradicts that thoseless likely to be doing 50 hours of continuing dental education are those with more years in practice and single-handed practitioners.12

However, private dental practitioners in Malaysiawho earn higher income participate in more numbers ofCPE than those who earn less. This agrees with Shugars etal.13 who said dentists who report higher incomes, attendmore continuing education. This can be associated withwhat Carrotte et al.14 found in his study, that the mostimportant barrier to participation is loss of income when dental practitioners attend CPE programs. Dental practitioners who report lower income may have constraintto participate in CPE, such as finding locum dentists, andthey avoid possible loss of income. This can be the reasonfor low participation in formal CPE among private dentalpractitioners in Malaysia.

Finding #2. Private dental practitioners learn in thecontext of practice and develop their skills by learningfrom experience, utilising increasing perception andintuitive recognition of systems within practical situations.

In terms of learning in non-formal CPE, majority ofprivate practitioners in Malaysia belonged to at least oneprofessional association and read at least one professionaljournal. Private dental practitioners who enrol in highernumber of professional associations, and who read/comment/write more journals participate in higher numberof CPE as compared to those of the opposites. Buckley &Crowley14 earlier indicated that dentists who actively participated in continuing dental education belonged tomore than one professional association, and subscribed tomore than one journal. However, about 20 percent of

10

Malaysian Private Dental Practitioners in Continuing Professional Education Context

private dental practitioners in Malaysia do not read journals at all and on the average, those who read only read3 journals in a year. When linking this to the learning preference in non-formal CPE, it can be said that privatedental practitioners in Malaysia prefer to learning fromexperience and peers, thus the low number of journalsread. This is congruent with Daley5 who pointed out thatfor professionals, experience, attendance at CPE programs,and dialogue with colleagues all contribute to the continual growth and refinement of meaningful knowledge. However, since dental profession is volatilewith changes in regulations, techniques, technologies andincreased expectation from the public, it is imperative thatdental practitioners get first hand knowledge and updatesfrom the most recent journals, rather than being reactive toexperiences and getting conveyer belt information fromtheir peers. Therefore, private dental practitioners learn inthe context of practice and develop their skills by learningfrom experience, utilising increasing perception and intuitive recognition of systems within practical situations.

Finding #3. Suitability of courses is not only seen fromthe clinical perspective, it includes courses that coverpersonal and professional development as well. Privatedental practitioners are highly selective in making decision to participate in CPE that are perceived to bebeneficial to them.

According to Tseveenjav et al.16 a dentist's field ofpractice and attitude towards CPE are the significant factors for participation. In Malaysia, the most significantfactor of participation in formal CPE among private dentalpractitioners is suitability of courses to the practice. This isfollowed by personal & professional development,reputation of instructor/speaker, hunger for knowledge,time/duration of CPE programs and reasonable fee. Thiscoincides with Daley5 who implies that new informationlearned in CPE programs is added to a professional’sknowledge through a complex process of thinking about,acting on, and identifying their feelings about new information, and it has to connect to other concepts beforeit is meaningful to them, and part of the process of makingknowledge meaningful is to use it in practice in some way.In reality, the elements of professional practice link withthe information from CPE programs to create meaning forpractice. This is further emphasised by Wiskott et al.,17

who found that the course contents should be aimed at satisfying the demands of practicing dentists, and thatbasic science issues and theoretical concepts should also be included. As indicated by some of the dental practitioners, suitability of courses should not only be seenfrom the clinical perspective, it should include courses thatcover personal and professional development as well. Thisis in line with what Nowlen18 discussed about theCompetence Model that current and relevant knowledgemust be combined with other skills (such as critical thinking or interpersonal relationship skills), personaltraits and characteristics (such as initiative or a sense of

ethics), an individual schema or self-image as a professional, and self-direction or a motive that serves to direct one’s action in practice. McGivncy19 also emphasised that the barriers to participation are centredaround the lack of advice and guidance on the opportunities available; lack of appropriate part-timecourses delivered in a way that is flexible to student’ timepressures; lack of affordable childcare, the levels of feescharged and the geographical constraints presented by having to travel to an often far location.

Some of the dental practitioners in Malaysia avoidloss of income that can occur while attending CPE by notgoing. This loss of income can happen when they have toclose their clinics due to failure in getting suitable locumdentists to substitute them while they are away. This can berelated to the time and days of courses scheduled for them.These factors should be the basis for providers of CPE inMalaysia to cater to the needs of these professionals.Private dental practitioners are highly selective in makingdecision to participate in CPE that are perceived to be beneficial to them.

Finding #4. Private dental practitioners perceive thatthey do not need to participate in CPE that are not relevant to their practice and not beneficial to them.

This conclusion is in harmony with that of Buckley& Crowley15 who found that there was a generally lowlevel of involvement in elements of CPE, such as attendance at scientific conferences, professional coursesand occasional meetings. As noted by Tseveenjav et al.,16 adentist's field of practice and attitude towards CPE are the significant factors for participation, whereas length of working experience, field of practice, holding a postgraduate degree, and having attended CE courses aresignificant factors for perceiving a need for CPE. However, since there is no significant difference in participation between and among groups in types ofemployment, graduation origin, level of qualification, agecategories, and period of practice, these factors do not significantly contribute to the participation in CPE amongprivate dental practitioners in Malaysia. Therefore,regardless of which group they are from, they may perceive that they do not need CPE, thus the low level ofparticipation in formal CPE.

This is contrary to the Update Model, CompetenceModel, or Performance Model due to the high wall of barrier, i.e. self-perceive. When they perceive they do notneed CPE, this becomes an ethical issue in the practice. Asstated by Lawler & Fielder,20 ethical problems arise whenpeople are faced with questions about fairness and aboutobligations owed to colleagues, customers, participants,and other stakeholders, in this case, to the patients and thesociety in which dental practitioners practice. Ethics setlimits regarding what people can do in pursuit of their owninterests, and prescribes standards of behaviour governingtheir dealings with others. CPE is seen as an ethical obligation to the dental practitioners towards themselves,

11

Razali / Rozima / Shamsuddin

their patients, and the profession. The low level of participation in formal CPE may be best explained throughSkill Acquisition Model that explains how professionalslearn.21

The emphasis is on learning from experience,utilising increasing perception and intuitive recognition ofsystems within practical situations, rather than actionbased on rote learning. As such, CPE providers mustrecognise these factors in constructing the framework ofcourses in order to increase the perception among theseprofessionals that CPE is worth participating and to makethem recognise the CPE providers as systems that are ableto provide relevant courses to their practical situations.When linking this to factors of participation, some of theprivate dental practitioners in Malaysia see CPE as notbeneficial to them and not worth the fees that are usuallyhigh. Some of them equate attending CPE with loss ofincome. Thus, dental practitioners who earn lower incomeparticipate in less CPE compared to those of higherincome because they want to avoid loss of income (See Finding #3).

Finding #5. Private dental practitioners do not see CPEas a tool to help them reaffirm their knowledge, to contribute to their personal growth and to increasetheir confidence.

Generally, private dental practitioners in Malaysiahave low attitude towards CPE. As noted by Tseeveenjavet al.,16 attitude towards CE is one of the significant factorsfor participation. Thus, the low level of attitude towardsCPE among private dental practitioners in Malaysia mayhave contributed to the low level of participation formalCPE among them. This is in line with Cross22 who postulated that learners must have a certain degree of self-confidence and a positive attitude to learning for them toengage in formal education. This contradicts the findingsby Daley5 who indicated that professionals have high attitude towards CPE as they see CPE as a tool to helpthem reaffirm their knowledge, contributes to their personal growth and increases their confidence. Therefore,the finding of this study suggests that the private dentalpractitioners in Malaysia do not see CPE as a tool to helpthem reaffirm their knowledge, to contribute to their personal growth and to increase their confidence. Whenrelating this to McGregor22 in his Theory X, suggested thatthe average person dislikes work (or in the case of thisstudy, the obligation to continuing pursuing education fordevelopment) and will avoid it if he/she can. Thereforemost people must be forced with the threat of punishmentto work towards the objectives. Realising the existence ofsuch situation, it may be a reason for the Ministry ofHealth to propose a mandatory CPE point system for dental practitioners in order to draw more crowds to CPEand to ensure continuous updating of current level of skillsand knowledge.

As what happened in the Philippines where dentalpractitioners are regarded as not adequately matured toreach a professional mindset to allow them to pursue continuing education voluntarily,24 perhaps it is time forthe Malaysian Government to think of a way to jumpstartan effort in promoting continuing professional educationas part of professional culture. O’Sullivan25 identified thatthe key features of clinical governance are accountabilityfor clinical performance and mechanisms for improvingclinical performance. Individual health professionals areexpected to be responsible for the quality of their own clinical practice. Furthermore, the determination of quality is closely aligned to clinical effectiveness, cost-efficiency and CPE. Maintaining quality in practice andimproving patient care requires individuals to keep up-to-date with practice, highlighting the need for research, auditand evidence-based practice. Perhaps, the step to introducemandatory CPE points for re-license would promote highattitude towards learning. CPE should be viewed as aninformation exchange system of creating and maintainingnetwork of communication among professionals.26 Suchnetworks are important to enhance one’s personal statusand relationships with others in establishing support andenhancing decision-making through wider informationgathering and exchange of ideas. Dental practitioners inMalaysia should be guided accordingly so that they wouldhave higher attitude towards CPE and be matured enoughto look at CPE from this point of view.

Finding #6. Private dental practitioners have low levelof self-perceived competence, self-confidence, self-image and success expectancy.

Since self-esteem is highly associated with self-confidence and high performance, the poor level of self-esteem among private dental practitioners in Malaysiashould be looked into seriously. Based on this finding, itcan be concluded that private dental practitioners have lowlevel of self-perceived competence, self-confidence, self-image and success expectancy. However, higher self-esteem is found among specialists, practitioners who areolder, who have longer period of practice, who participatein higher number of CPE, and who have higher attitudetowards CPE. Generally, when they complete a task, largeand small, they feel proud of their accomplishment, but arehurt by other’s opinions or attitudes. This is congruent withHamid & Mohamad2 who noted that individuals with lowself-esteem show such symptoms as depression, anxiety,the attitude of attribution of their defeats to others, anddecrease in performance, lack of educational success andinterpersonal problems. They continued to say that newskills and increasing abilities are among the important factors in creating self-esteem. Therefore, to increase self-esteem among dental practitioners, they must engage inmore CPE because Moner27 indicated that individuals withhigh self-esteem have higher self-perceived competence,self-image and success expectancy.

12

Malaysian Private Dental Practitioners in Continuing Professional Education Context

Baumeister et al.3 concluded that in performancecontext, high self-esteem people appear to use better self-regulating strategies than low self-esteem people. Thisserves as a strong foundation for effective CPE point system for dental practitioners in Malaysia. It is in linewith the nation’s aspiration to embark on health/dentaltourism. Private dental practitioners should have soundself-esteem to successfully meet increased demand inpatients’ care and greater expectations from local communities, foreign tourists and expatriates. They mustbe as adequately competent as their peers in other countries in order to acquire the confidence among foreigners who seek dental care in Malaysia. This will provide greater opportunities for Malaysian private dentalpractitioners to extend their service and acquire international experience in other countries.

Finding #7. The missing link is the attitude towardsCPE. Low level of attitude towards CPE explains thelow level of participation in CPE and serious handicaplevel of self-esteem among private dental practitioners.

There are significant positive relationships betweenparticipation in formal CPE and self-esteem, attitudetowards CPE and self-esteem, age and self-esteem, periodof practice and self-esteem, between attitude towards CPEand participation in formal CPE, and between attitudetowards CPE and period of practice. Practitioners who areolder and who have been in practice for longer period havehigher self-esteem. Thus this group of practitioners isexpected to engage more in CPE.

However, the findings showed that participationdoes not have significant relationship with age and periodof practice. Thus, the missing link here is the attitudetowards CPE. Low level of attitude towards CPE explainsthe low level of participation in CPE and serious handicaplevel of self-esteem among private dental practitioners.That means when the attitude towards CPE is high, privatedental practitioners will engage in more CPE, thus increasing the level of self-esteem and enhancing theimage of this profession among these professionals.Nevertheless, in general, the current level of attitudetowards CPE among private dental practitioners inMalaysia is low. If the attitude towards CPE can beincreased, this will add to the participation in CPE and willboost the self-esteem among private dental practitioners.

As Daley5 clearly noted, professionals should notsee transfer of learning as an outcome of their educationalendeavours; they must view transfer of learning as an integral part of the meaning-making process. New information learned in CPE programs is added to a professional’s knowledge through a complex process ofthinking about, acting on, and identifying their feelingsabout new information. Therefore, rather than debating themandatory issue or arguing whether competency standardsare appropriate for professionals, a preferable alternativemight be to focus on lessening the problems associatedwith CPE as a tool for improving professional practice as

in the case of this study, the low level of attitude towardsCPE among private dental practitioners. As mentioned earlier, CPE should not be seen as an extension to theknowledge base of universities. It should be viewed as aninformation exchange system of creating and maintainingnetwork of communication among professionals.26 Suchnetworks are important to enhance one’s personal statusand relationships with others. They are important in establishing support and enhancing decision-makingthrough wider information gathering and exchange ofideas. Dental practitioners in Malaysia should be guidedaccordingly so that they would have higher attitudetowards CPE and be matured enough to look at CPE fromthis point of view.

CONCLUSION

The findings implied that private dental practitioners who join higher number of professional associations, who read/comment/write higher number ofjournals, and who earn higher income, participate in higher number of CPE. Private dental practitioners showedhighest preference to learning from experience and frompeers. The utmost important factor of participation in CPEwas suitability of courses to practice. However, the level ofparticipation in CPE was found to be far below the expectation, the level of attitude towards CPE was low, andthe level of self-esteem among private dental practitionersin Malaysia was of serious handicap. Significant relationships were established between attitude towardsCPE and participation in CPE, between participation inCPE and self-esteem, and between attitude towards CPEand self-esteem.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to acknowledge the contribution andsupport of Dato’ Dr. Wan Mohamad Nasir b. Wan Othman,the Director of Oral Health Division, the Malaysian PrivateDental Practitioners’ Association, Westminster ConsultingSdn Bhd and Universiti Putra Malaysia for this study.

REFERENCES

1. Information and Documentation System Unit, Planning &Development Division. Ministry of Health Malaysia. HealthFacts. 2003. Retrieved from www.gov.moh.my

2. Hamid RA, Mohamad RA. The Relationship Between Self-Esteem and Job Satisfaction of Personnel in GovernmentOrganizations. Public Personnel Management. 2003:32(4).

3. Baumeister RF, Campbell JD, Kruger JI, Vohs KD. DoesHigh Self-Esteem Cause Better Performance, InterpersonalSuccess, Happiness, or Healthier Lifestyles? PsychologicalScience in the Public Interest, 2003:4(1).

13

Razali / Rozima / Shamsuddin

4. Orpen C. The Impact of Self-Efficacy on the Effectiveness ofEmployee Training. Journal of Workplace Learning.Employee Counseling Today. 1999;11:119-22.

5. Daley BJ. Learning and Professional Practice: A Study ofFour Professions. Adult Education Quarterly. 2001;52:39-54.

6. Kerlinger FN. Foundations of Behavioral Research, NewYork. 1986. Holt, Riverhart & Winston.

7. Alreck PL, Settle RB. The Survey Research handbook, 2ndEd., 1995. Chicago: Irwin.

8. Krejcie RV, Morgan DW. Determining Sample Size forResearch Activities. Educational & Psychological Measurer.1970;30:607-610.

9. Ary D, Jacobs LC, Razavieh A. Introduction to Research inEducation. 5th Ed., 1996. Harcourt Brace College Publishers.

10. Gay LR. Educational Research: Competencies for Analysisand Application. 3rd Ed., 1987. Meirill, Columbus, USA.

11. Buck D, Newton T. Continuing Professional Developmentamongst Dental Practitioners in United Kingdom: How farare we from lifelong learning targets? European J Dent Educ.2002;6:36-9.

12. Bullock A, Firmstone V, Fielding A, Frame J, Thomas D,Belfield C. Participation of UK Dentists in ContinuingProfessional Development. Br Dent J. 2003;194:47-51.

13. Shugars DA, DiMatteo MR, Hays RD, Cretin S, Johnson JD.Professional satisfaction among California General Dentists.J Dent Educ. 1990;54:661-9.

14. Carrotte PV, Walker ADM, Rennie JS, Ball G, Dodd M.Personal learning plans for General Dental Practitioners: AScottish perspective - Part 2. Br Dent J. 2003;194: page

15. Buckley GJ, Crowley MJ. The Continuing Dental Education(CDE) activities of a Regional cohort of Irish Dentists - Abaseline study. J Ire Dent Assoc. 1993;39:54-9.

16. Tseveenjav B, Vehkalahti MM, Murtomaa H. Attendance atand self-perceived need for ontinuing education amongMongolian dentists. European J Dent Educ 2003;7:130-5.

17. Wiskott HW, Borgis S, Simoness M. A Continuing EducationProgram for General Practitioners. Status Report after 5 yearsof function. European J Dent Educ. 2000;4:57-64.

18. Nowlen P. A new approach to continuing education for business and the professions: the performance model. 1988,Old Tappan, NJ.: Macmillan.

19. McGivncy V. Women, education and training: barriers toaccess, informal starting points and progression routes. 1993,National Institute of Adult Continuing Education and HilcrottCollege, London.

20. Lawler P, Fielder J. Ethical problems in continuing highereducation: Results of a survey. J Continuing Higher Educ.1993;41:25-33.

21. Dreyfuse H, Dreyfuse S. Mind over machine: the power ofhuman intuition and expertise in the era of the computer.1985, New York: Free Press.

22. Cross P. Adults as learners. 1982, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

23. McGregor D. The Human Side of Enterprise, 1960, bookpublisher and city?

24. Philippine Dental Association. CPE as a compulsory requirement for membership in PDA: A justification. 2003.

25. O’Sullivan J. Research in post-compulsory education. 2003,Volume 8, Number 1.

26. Chambers D. The continuing education business. J DentEduc. 1992;56:672-679.

27. Moner 1992???

Address for correspondence:

Dr. Abu Razali Saini,Malaysian Private Dental Practitioners’ Association,c/o Malaysian Dental Association,54-2, Medan Setia 2, Plaza Damansara50490 Kuala Lumpur, MalaysiaTel : 603-20951532Fax: 603- 603-20944670Email: [email protected]

14

Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma – Relevant Laboratory DiagnosisSolomon MC Professor, Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, Manipal College of Dental Sciences, Manipal576104, India.

Rao NN Professor and Head, Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, Manipal College of Dental Sciences,Manipal 576104, India.

Carnelio S Associate Professor, Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, Manipal College of Dental Sciences,Manipal 576119, India.

ABSTRACTOral Squamous cell carcinoma is a serious oral health problem. The structure and behavior of this neoplasm varies greatly.Advances in scientific technology, has paved the way to comprehend the genetic changes a keratinocyte undergoes during carcinogenesis. The knowledge of the molecular mechanism underlying this neoplasm enables assessment of its behaviour andabove all is the foundation for developing biologic therapeutics to target specific molecules. A few relevant diagnostic modalities are briefly described and their importance highlighted

Key words:Squamous cell carcinoma, diagnosis, behaviour, prognosis

The progression of an oral keratinocyte from itsnormal status to dysplasia and eventually to neoplasia is amulti-step process involving many complex factors. Therehave been numerous scientific approaches aimed at understanding the biochemical aspects of the developmentand progression of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC).Grading of the tumor relies greatly on the light microscopyexamination of hematoxylin and eosin stained tissue sections. However, histological assessment is less reliableas there is considerable inter and intra examiner variations.Over the years with more sophisticated scientific technology, the behavior of tumor cells is more clearlydetermined. This article intends to describe some of thediagnostic methods that are employed for diagnosis andprognostication of Squamous cell carcinomas of the oralcavity

Exfoliative Cytology

Exfoliative cytology is a rapid, non-invasive procedure that was primarily used in the screening of theuterine cervix for dysplasia and carcinoma. With the introduction of alcohol-based stains by Papanicalaou,examination of smears was simplified and standardized.This facilitated its use in the early diagnosis of oral squamous celI carcinomas. It is also used for assessingpotentially malignant lesions

The exfoliated cells of OSCC exhibit features ofincreased keratinization, increased nuclear area, increasednuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, nuclear pleomorphism, nuclear-hyperchromatism and Chromatin clumping1 (Fig 1).

With recent advances in immunohistochemistry,cytophotometry and DNA analysis of smears, there has bean reappraisal of the value of exfoliative cytology in thediagnosis of oral cancer2

Histopathology

Histopathologic grading of squamous cell carcinoma represents the anticipated biological behavior ofthe neoplasm. Broder initiated a quantitative grading systemfor Squamous Cell Carcinomas. This classification system is based on the estimated ratio of differentiated to undifferentiated elements in the tumor.3 However, as squamous cell carcinomas usually exhibit a heterogenouscell population with differences in the degree of differentiation, it is difficult to determine the prognosis of thetumor by this system.4 A new multi-factorial grading systemput forth by Anneroth emphasizes on the morphologic features of tumor cells, the degree of differentiation of thecells and the tumor host response5 (Fig 2). In addition; Bryneet al found that deep invasive tumor cells appeared to be histologically less differentiated than cells in the more superficial parts.6 Thus, malignancy grading at the invasivemargins (‘Invasive front grading”) has shown to be of higher prognostic value

Malaysian Dental Journal (2006) 27(1) 14-19© 2006 The Malaysian Dental Association

MALAYSIAN DENTAL JOURNAL

15

Solomon / Rao / Carnelio

Histochemistry

The application of special stains such as PeriodicAcid Schiff (PAS) is becoming a part of routine histology.PAS stain reveals the loss of glycogen content in the dysplastic epithelium, areas of discontinuity of the basement membrane and colonies of candidal hyphae.7 Byobserving the staining pattern of the basement membranein PAS stained sections, areas of tumor invasion can beidentified. (Fig 3)

Nucleolar organizer regions (NORs) are segmentsof chromosomes that are encoded for rRNA and are present on specific loops of DNA. Some of the NOR associated proteins can be demonstrated as black dots ofby silver staining techniques and are know as AgNORs.8 Inpoorly differentiated OSCC, AgNORs appear as exceedingly numerous tiny black dots that are more irregular in size and shape (Fig 4) than the AgNORs inwell- differentiated OSCC. The number of AgNORs pernucleus reflects the rate of cellular proliferation of the neoplasm and a higher AgNOR count suggests a poorprognosis.9

Immunohistochemistry

The advent of monoclonal antibodies to various cellular antigens resulted in discovery of several tumor markers.Immunohistochemical methods recognize antigen-antibody complexes with the help of a chromogen. lmmunohistochemical techniques have an. advantage overother techniques because the tissue architecture is intact, thecell-cell relationship is maintained and proliferating cells can be visualized in relation to other histological features.Immunohistochemical techniques can be utilized to identifyepithelial surface antigens, intercellular products,constituents of the basement membrane, markers of cell proliferation, and changes in the adjacent connective tissuestroma, oncogenes and oncosupressor genes.

Immunohistochemical staining procedures havedemonstrated overexpression of Epidermal growth factor(EGFR) in OSCC. EGFR immunoreactivity extends to alllayers of the epithelium in OSCC.10 Higher levels of EGFRmight enable tumor cells to respond to low levels of epidermal growth factor that is not mitogenic to normalcells.11 Overexpression of EGFR also predicts a decrease inpatient survival.12

Cytokeratins are intermediate filament proteinthat maintains the cytoskeletal framework of epithelialcells. Immunohistochemical techniques carried out onfrozen tissue samples using a panel of antibodies againstsimple keratins revealed variations in the keratin profilesaccording to the tumour differentiation. Analysis of keratin expression refines both tumour diagnosis and subsequently prognosis13 Keratin expressions have alsobeen used to determine whether a poorly differentiatedtumour is of epithelial or mesenchymal origin.14

Laminin, a basement membrane associated glycoprotein is distributed exclusively in the epithelial portion of the basement membrane.

Immunohistochemical staining reveals the presence of laminin in invasive tumors with well definedtumor host borders and cohesive patterns of stromal invasion (Fig 5). Invasive carcinomas with irregular cordsor single tumour cells distributed throughout the host stroma invariably lack laminin at the tumor-host interface.15 The balance between basal lamina productionand degradation is an important aspect of tumor invasion.Tumor cells that can produce basement membrane components belong to differentiated cell phenotype.16

Tenascin is extracellular matrix glycoprotein synthesized by fibroblasts and muscle cells. It appears tobe involved in epithelial mesenchymal interactions duringembryogenesis and tumor development and acts as a signaltransduction extracellular protein. Squamous cell carcinomas almost invariably show intense and extensivestromal tenascin immunoreactivity being more distinct atthe advancing edges of the tumor islands.17 Expression oftenascin is closely associated with invasive and metastaticpotential of the tumor.18

Proliferation of cells is the key characteristic feature of a tumor. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen(PCNA) is a 36KD, non-histone acidic nuclear proteinwhich is synthesized in the G1 and S phase of a cell cycle.It is necessary for cell cycle progression and cellular replication.l9 Increased expression of PCNA is seen only inwell differentiated and moderately differentiated squamous cell Carcinomas. While the proliferating cells inpoorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma are in astate of the cell cycle with undetectable levels of PCNA20

Oncogenes may be associated with differentstages of neoplasia. Immuno-reactivity of C-myc oncogene is seen in the nucleus, perinuclear cytoplasm andentire cytoplasm of cells in the mitotic phase. The expression of these genes is found among the proliferatingcells of the tumour.21 Over expression of the ras family ofgenes occurs commonly in squamous cell carcinomas ofthe head and neck region. Immunohistochemical studieshave shown that the expression of these genes was more inlarger tumors and in the later stages of the tumourigenesis.22

Oncosuppressor genes are regulators of cell proliferation. P53 gene produces a protein that usuallyblocks the progression of cell growth. Mutations in the p53gene are found to be the most common genetic alterationin OSCC. Immunohistochemical techniques detect mutantforms p53 (Inactive p53). Elevated levels of p53 gene arefound in patients who are heavy smokers and alcoholics.This indicates that the carcinogens in tobacco and alcohol are responsible for the mutations in the p53 oncosuppressor gene.23

16

Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma – Relevant Laboratory Diagnosis

Fig 1: Photomicrograph showing exfoliated oral epithelialcells exhibiting Nuclear hyperchromatism and increasednuclear-cytoplasmic ratio (Papanicalaou stain-40X)

Fig 2: Photomicrograph showing highly keratinized,well delineated tumor Islands exhibiting mild nuclearpleomorphism invading the lamina propria and a moderate lympho-plasmacytic infiltration.(Haematoxylin and Eosin-10X)

Fig 3: Photomicrograph showing absence of basementmembrane and presence. Of tumor islands in the lamina propria (Periodic Acid Schiff stain -10X)

Fig 4: Photomicrograph showing increased number ofsmall, well separated AgNORs in the nucleus of tumorcells in Oral Squamous cell carcinoma (Silver stain-40X)

Fig 5: Photomicrograph showing the expression oflaminin in the basal lamina around tumor islands.(Immunohistochemical stain -40X)

Fig 6: Photomicrograph showing bright and uniforminter-cellular substance demonstrated by indirectimmunofluorescence in tumor islands(Immunoflourescent stain 40X)

17

Solomon / Rao / Carnelio

Immunofluorescence

The cell surface of malignant cells exhibits profoundalterations. It could be loss of surface antigens or the appearance of new antigens. Indirect immunofluorescencewith sera from pemphigus patients can demonstrate intercellular substance (ICS) antigen (Fig 6). Absence of lCSreactivity indicates the presence of cellular atypia.24 The intensity and pattern of immunofluorescence staining is related to the degree of differentiation. Few individual cellsshow intercellular substance reactivity in highly anaplasticsquamous cell carcinoma. Antigen loss represents impaireddifferentiation of neoplastic cells and which facilitates localtumour invasion.25

Electron Microscopy

Although, ultrastructural studies may not be utilizedmuch in routine diagnostic procedure, it can add to understandthe biology of the disturbances in epithelial differentiation incarcinomas. The changes observed are alterations of nucleiand nucleoli, cellular organelles, tonofibrils, cell membrane,desmosomes, and basement membrane. Loss or decrease inthe number of keratohyaline granules. dyskeratosis necrosis,Fibrillar dyskeratosis ,formation of immature keratin withremnants of organelles, lack of stable membrane formationand organoid keratosis( Keratin pearls).26 Electron microscopicstudies have also shown that malignant cells are ovoid,pleomorphic and larger compared to normal epithelial cells27

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry is a fast and automated techniqueof measuring the nuclear DNA content of 20,000-50,000cells with accuracy, resolution and reproducibility.28 Flowcytometric analysis enables elucidation of characteristicfeatures of malignant tumor cells that cannot be clarifiedby routine histopathological methods. In OSCC as thedegree of differentiation decreases from well to poor theincidence of aneuploidy increases.29 Patients with diploidtumors have a significantly longer relapse- free and survival period than those with aneuploid tumors.30

In-situ hybridization

In-situ hybridization permits the direct analysis ofDNA or RNA in tissues. Thus, specific cells, population ofcells or chromosomes can be detected. This method is a.combination of advanced technology and light microscopyfor detecting virus infected cancer cells. The host cell forHuman Papilloma virus (HPV) is a keratinocyte and theviral genome can be detected by localization of a specificHPV DNA sequence, In situ hybridization with HPV-16DNA, probes shows nuclear hybridization in well-differentiated parts of the tumour while in poorly differentiated areas hybridization is absent.31

Southern Blot hybridization

This is a molecular technique for the analysis ofgenes wherein oncogene probes are utilized to identifygene amplification; Oncogene C,erb-.l is amplified andoverexpressed in oral carcinoma cell lines.32 A 2 fold-11fold amplification of Int-2 oncogene has been detected inSquamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck.33

Polymerase chain reaction

OSCC subjected to Polymerase chain reactiontechnique show cells containing DNA HPV 16, HPV 6,and HPV 18. This supports the concept of HPV as an etiological factor of OSCC wherein the virus probably actssynergistically with other carcinogens.34

Analysis of cell products in circulating blood

Serum markers that are of prognostic value fororal squamous cell carcinoma are mainly immune-related circulating substances such as immune complexes, complement binding molecules. interlukins.immunoglobulins and leukocytes.35 Elevated serum levelsof complement binding molecules and IgA was found tosignify a poor prognosis.36

Serum level of _2 microg1obulin is increased inpatients with Squamous cell Carcinoma. _2 microglobulin isa cell membrane component that is related to HLA domain.An accelerated cell membrane turnover or accelerated celldivision could increase its release into the circulatory system.Malignant cells release _2 microglobulin more rapidly thannormal cells37

Laser Spectroscopy

Small primary tumours shed viable tumour cells, anentire array of enzymes and surface molecules into the circulatory system. Techniques have made use of the presenceof these bimolecular in physiological samples like blood andsaliva for early detection of tumors. Defensin 1 a specific peptide has been detected in the saliva of OSCC patients.38

Laser induced fluorescence spectroscopy is capable of detecting and recording the spectra of sub picograms of proteins as they flow past a probing laser beam.39

Oral squamous cell carcinoma is a life threatening disease of oral tissues. Its pathogenesisincludes dysplastic transformation of normal oral epitheliafollowed by invasion into the underlying connective tissue.Although the assessment of the biological potential ofOSCC relies on light microscopic histological examination, more sensitive tests are employed to identifytumor markers. These tumor markers have become diagnostic tools as they herald malignant transformationand some have been found to be excellent prognostic indicators. Advances in immunohistochemical techniquehas opened avenues for single formalin fixed, paraffinembedded biopsy specimen to be subjected to a battery of

18

Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma – Relevant Laboratory Diagnosis

monoclonal antibodies. The major recent advance in cancer research hopes to unravel the molecular mechanisms of oncogene activation.

The various diagnostic modalities (Table 1)enable an accurate assessment of tumor behavior and prog-nosis of individual cases, monitor the response to therapy,and provide the necessary information for formulating spe-cific and effective treatment regimes.

TABLE 1

DIAGNOSTIC IMPLICATIONMODALITY

Exfoliative Cytology Cellular atypia of exfoliated cells

Histopathology Grading of tumor

Identify changes in the basement membrane that

Histochemistry signifies tumor invasionDetect Nucleolar Organizer regions and identify proliferative cells

Expression of markers of cellular proliferation,

Immunohistochemistry basement membrane and cytoskeletal components,oncogenes and oncosu-pressor genes

Detect the presence or Immunofluoroscence absence of antigens of the

inter-cellular substance among tumor cells

Electron Microscopy Shows the Ultra structural features of malignant cells

Flow Cytometry Demonstrates Aneuploidy of tumor cells

In-situ Hybridization Viral genomes in the nucleus of tumor cells

Southern blot hybridization Enables amplification of oncogenes

Polymerase Chain reaction Viral genomes in the nucleus of tumor cells

Serum Analysis Presence of tumor markers in serum

Laser spectroscopy Detects biomarkers in serum and saliva

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Mr Shreepathy Upadhyaya, Senior Technician,Department of Oral Pathology, MCODS, Manipal

REFERENCES

1) Philip B, Neil W. Exfoliative cytology in clinical oral pathology. Australian Dental Journal 1996;41:71-74

2) Ogden O R, Cowpe J G, Wright A J. Oral exfoliative cytology: review of Methods of assessment. J Oral PatholMed 1997:26;201-205

3) Broders A C The microscopic grading of cancer Surg ClinicNorth Am 1941;21:947-962

4) Stoddart T G. Conference of cancer of the lip. J Can MedAssoc 1966;90:666-670

5) Anneroth G, Batsaki J, LunaM. Review of literature and arecommended system of malignancy grading in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Scand J Dent Research1987;95:229-249

6) Bryne M, Jenssen N, Boysen M Histological grading in thedeep invasive front of T1 and T2 glottic squamous cell carcinomas has high prognostic value Virchows Arch1995;427:277-281

7) Doyle J L, Manhold J H, Weisinger E. Study of glycogencontent and Basement membrane in benign and malignantlesions Oral Surg 1968;26:667

8) Warnakalasuriya K A A S, Johnson N W. Nucleoar organizerregion (NOR) as a diagnostic marker in oral keratosis,dysplasia and oral squamous cell carcinoma. J oral PatholMed 1993;22:77-81

9) Sana K, Takahasi H, Fujita S. Prognostic implications of silver binding nucleolar organizer region (AgNORs) in oralsquamous cell carcinoma J Oral Pathol Med 1991;20:53-56

10) Shirasuna K, Hayashido 'Y, Sugiyama M et al.Immunohistochemical localization of epidermal growth factor and EGF receptor in human oral mucosa and its malignancy. Virchows Archiv A pathol Anat 1991;418: 349-353

11) Kawamoto T, Sato J D, Polikoff A L J et al Growth stimulationof A431 cells by epidermal growth factor: identification of highaffinity receptors for epidermal growth factors by an anti-receptor monoclonal antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA1983;80:1337

12) Hendler F J, Shum-Siu A, Oescheli M et a1. Increased EGF-R binding predicts a poor survival in squamous tumors.Cancer cell 1989;7:347-351

13) Ogden O R, Chisholm D M, Adi M, Lane E B. Cytokeratinexpression in Oral cancer and its relationship to tumor differentiation J Oral Pathol Med 1993;22:82-86

14) Macluskey M, Ogden G R. Overview of the prevention oforal cancer and diagnostic markers of malignant change: 2.Markers of value in tumor diagnosis Dent Update2000;27:148-152

15) Meyer J R, Silverman S, Daniels T E, Kramer I R H,Greenspan J S. Distribution of fibronectin and laminin in oralleukoplakia and carcinoma J Oral Pathol Med 1995;14:247-255

16) Sakr W A, Zarbo R J, Jacob J R, Crissmann J D. Distributionof basement membrane in squamous cell carcinoma of headand neck. Human Pathol 1987;18:1043-1050

17) Tiitta 0, Happonen R P, Virtanen I. Distribution of tenascin inoral premalignant lesions and Squamous cell Carcinoma JOral Pathol Med 1994;23 (10): 446-450

19

Solomon / Rao / Carnelio

18) Harada T, Shinohara M et al. An immunohistochemistrystudy of extra cellular matrix of oral squamous cell carcinoma and its association with invasive and metastaticpotential. Virchows Archives 1994;424:257-266

19) Tsai S T, Jin Y T. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral PatholMed 1995:24:313-315

20) Mohanty L, Rao N N , Kotian M S Expression of proliferatingcell nuclear antigen (PCNA) in Leukoplakia and Squamous cellcarcinoma-An immunohistochemical study. Malaysian Dent J2002;23(1):65-71

21) Sakai H, Kawano K, Okamura K, Hashimoto N.Immunohistochemical loclization of C-myc oncogene product and EGF receptor in oral squamous cell carcinoma. JOral Pathol Med 1990;19(1):1-4.

22) Mc Donald J S, Jones H, Pavelic Z P, Pavelic LJ, StambrookP J, Gluckman J L. Immunohistochemical detection of the H-ras, K-ras and N-ras oncogene in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck J Oral Pathol Med1994;23:342-346

23) Field J K, Spandidos D A, Malliri A, Yiagnisis M, Gosney JR, Stell P M Elevated p53 expression with a history of heavysmoking in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck BrJ Cancer 1991;64:573-577

24) Tosca A, Varelzidis A, Nicolis G et al: Antigenic alterationsin tumors of epidermal origin. Cancer 1980;45:2284-2290

25) Bovopolou 0, SkIavounou A, Laskaris G. Loss of intercellularsubstance antigen in oral hyperkeratosis, epithelial dysplasiaand squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol1985;60:648-654

26) Burkhardt A. Advanced methods in the evaluation of premalignant lesions and carcinoma of the oral mucosa. J OralPathol Med 1985;14:751-778

27) Sow yeh Chen, Robert D. Ultrastructural findings in oralsquamous cell carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol1977:744-753

28) Jalal Uddin M, Ruey-Bin C et al. Flow cytometric analysis ofsquamous cell carcinomas of the oral and maxillofacialregion with review of literature Indian J Dent Research1996;7(3) 81-95

29) Chen R B. Flow cytometric analysis of benign and malignanttumors of the oral and maxillo facial region. J OralMaxillofacial Surg 1989;47:596-560

30) Goldsmith M M, Cresson D H, Arnold L A et al. DNA flowcytometry as a prognostic indicator in head and neck cancer.Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;96:307-318

31) Milde K, Loning T. Detection of papilloma virus DNA in oralpapillomas and carcinomas-application of in-situ hybridizationwith biotinylated HPV 16 probes. J oral Pathol Med1986;15:292-296

32) Yamamoto T, Kamata N, Kawano H et al. High incidence ofamplification of epidermal growth factor gene in humansqnamous carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Res 1986;46:414-416

33) Merritt W D, Weissler M C, Turk B F, Gilmer T M. Oncogeneamplification in squamous cell carcinoma of the head andneck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;116:1394-1398

34) Chang F, Syrjanen S, Nuutinen J, Syrjanen K. Detection ofhuman papilloma (HPV) DNA in oral squamous cell carcinoma by in-situ hybridization and polymerase chainreaction. Arch Dermatol Res 1990;282(8):493-497

35) Cohn S L, Lincoln ST. Present status of serum tumour markers in the diagnosis, prognosis evaluation of therapy.Cancer Invest. 1989;4:305-327

36) Schantz S T, Liu F J, Taylor D et al. The role of circulatingIgA to Cellular immunity in head and neck cancer patientsLarnygoscope 1998;98: 671--678

37) Manzar W, Raghavan M R V, Arror A.R, Murthy K R.Evaluation of serum _2 microglobulin in oral cancer. AustDent J 1992;37:39-42

38) Mizukawa N, Sugiyama K. Fukunaga J, et al. Defensin-l. apeptide detected in the saliva of oral squamous cell carcinoma patients. Anticancer Res 1998;18(6):4645-4649

39) Kartha.V B, Venkatakrishna K. Dept of Science andTechnology project. Govt of India "Investigation of Laserspectroscopy methods of early diagnosis of neoplasia:Development of instrumentation and analytical Techniques"project no. SP/SL/LOl/98

Address for correspondence:

Professor Dr. Monica SolomonProfessorDepartment of Oral Pathology and Microbiology,Manipal College of Dental Sciences,Manipal 576104, India.Email: [email protected]

20

Amelogenesis Imperfecta with Gingival Hyperplasia and Anterior Open Bite –A Case ReportMadhu S. Senior Lecturer in Paedodontics, Govt. Dental College, Kozhikode, Kerala (state), India – 673008.