AWARD_14085

-

Upload

nirmalkumaar88 -

Category

Documents

-

view

242 -

download

0

description

Transcript of AWARD_14085

INDUSTRIAL COURT OF MALAYSIA

CASE NO. 10/4 - 592/05

BETWEEN

CARSEM (M) SDN BHD

AND

ENCIK GOPALA KRISHNAN A/L K. VELLASAMY

AWARD NO. 1012 OF 2010

Before : Y.A. PUAN CHOONG SIEW KHIMCHAIRMAN (Sitting Alone)

Venue : Industrial Court of Malaysia, Perak Branch

Date of Reference : 28 April 2005

Dates of Mention : 5.7.2005, 9.8.2005 and 13.9.2005 Dates of Hearing : 28.6.2006, 5.3.2007, 1.10.2007, 2.10.2007, 28.5.2008 and 29.5.2008

Company's Written Submissions : 27 June 2008

Claimant's Written Submissions : 27 July 2009

Company's Written Submissions-In-Reply : 7 April 2010

Date of Final Oral Submissions : 28 July 2010

Representation : Mr. Mohan Ramakrishnan Messrs. Ramakrishnan & Associates

Advocates & SolicitorsLearned Counsel for the Claimant

Mr. S. Gunasegaran with Mr. S. Nanda KumarMessrs. A. M. Ong & PartnersAdvocates & SolicitorsLearned Counsel for the Company

1

AWARD

The Reference:

With effect from 3.8.2004, Gopala Krishnan a/l K. Vellasamy (called ‘the Claimant’

hereon-in) ceased from his service with Carsem (M) Sdn. Bhd. (referred to as ‘the

Company’ hereinafter). The Claimant having considered himself unjustly dismissed

by the Company at or about that time, made written representations to the Director-

General for Industrial Relations pursuant s. 20 of the Industrial Relations Act, 1967.

These representations were made on 30.8.2004. Later and after due process, the

Honourable Minister of Human Resources, Malaysia by an order transformed the

Claimant’s representations into a reference before this Court. The ministerial edict

was dated 28.4.2005; it was acknowledged by the Court’s Registry at Kuala Lumpur

on 31.5.2005 and subsequently by this Division of the Industrial Court at Ipoh, Perak

on 14.6.2005.

A Point of Embarkation:

The preliminary administration of this matter was carried out on mention dates fixed

between 5.7.2005 and 13.9.2005. The trial was initially set-down to commence on

28.6.2006, on which date the matter was taken off as the then learned Counsel for

the Claimant was said to have been taken ill. New hearing dates were fixed for 5 &

6.3.2007. On 5.3.2007 the matter was again adjourned, this time at the instance of

learned Counsel for the Company as he had just been served with the Claimant’s

bundle of documents. He needed time to study the same and take instructions

2

thereupon. As there were no objections from the Claimant’s side, new hearing dates

were fixed to fall on 1 & 2.10.2007. Thus, did the trial commence on 1.10.2007 and

continued there from, from time to time, until 29.5.2008. It is to be acknowledged

that the entire hearing of this matter was conducted before Y.A. Madam Choong

Siew Khim, the then Chairman of this Division. At the request of both the parties

hereto, that Learned Chairman directed that written submissions be filed by the

respective parties. To that end, submissions for and on behalf of the Company was

filed on 27.6.2008; and for and on behalf of the Claimant on 27.7.2009.

Subsequently, a submission-in-reply for and on behalf of the Company was filed on

7.4.2010.

In the interregnum, on or about 16.2.2009, the then presiding officer of this Division

was transferred to another place of duty at Kuala Lumpur; and afterwards on

14.8.2009 the said officer, Y.A. Madam Choong Siew Khim, was appointed as a

Judicial Commissioner of the High Court of Malaya. As a result of that appointment,

Her Ladyship became functus officio in this case.

On receipt of the Company’s submission-in-reply on 7.4.2010, this Court directed its

Interpreter, Ms. Vinothini, to contact the respective Solicitors’ of the parties hereto

and inquire if one or both had any objections to the current presiding Chairman of

this Division taking over the further conduct of this reference. Both parties, through

their Solicitors’, expressed no objections subject to being allowed to address the

Court with further and final oral submissions. The matter was then fixed on

28.7.2010 to facilitate this request; where both learned Counsel for the Company

3

and the Claimant elaborated upon and highlighted the salient points of the case from

their respective perspectives.

In support of the preparation of this Award I have had the benefit of the perusal of

the notes of evidence based on the verbatim record of Y.A. Madam Choong Siew

Khim; in conjunction with having had sight of the documentary evidence tendered in

this case; together with having heard the final oral submissions of both learned

Counsel juxtaposed with the study of the written submissions filed for and on behalf

of the respective parties hereto.

All that remains now is the handing down of the Award; which duty I shall undertake

herein below.

The Facts:

The Claimant commenced employment with the Company on 1.12.1995 in the

capacity of “Section Head” in the rank of “Executive Grade C2” at a salary of

RM3,500.00 per month [see Letter of Appointment dated 27.11.1995 - @ - bundle marked

CLB 1, at pages 2 to 4]. The Claimant was emplaced at the Company’s “M-Site”. He

was confirmed in this appointment with effect from 1.6.1996 [see Letter of Confirmation

dated 21.6.1996 - @ - bundle marked CLB 1, at page 5]; and “in line with the

standardization of job titles exercise” the Company designated him as “Section

Manager” with effect from 20.8.1997 [see letter entitled “Change of Job Title” dated

20.8.1997 - @ - bundle marked COB 2, page 6].

4

The Claimant remained in that position until in or about the month of July 2002 when

he was transferred to the Company’s “S-Site”, in a similar capacity of “Section

Manager”.

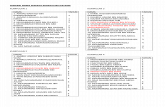

The Claimant continued in that job until 2.8.2004, on which date he issued a letter to

the Company wherein he (the Claimant) communicated his conviction of having been

constructively dismissed by the Company, which was to take effect from 3.8.2004

[see pages 9 & 10 of bundle marked CLB 1 – reproduced below].

5

6

The Claimant contends that the Company, through the particular officer named in the

letter above, had committed a variety of acts which amounted to a repudiatory

breach of his contract of employment; and by this had driven him out of employment.

He prayed to be reinstated to his former position without loss of seniority, wages or

benefits, monetary or otherwise, together with arrears of salary.

The Company, needless to say, denied the Claimant’s allegations and contended

instead that the Claimant had walked-out of his employment on his own volition. The

Company averred that it had not by itself committed any acts against the Claimant

that could be construed as a breach of contract entitling the Claimant to claim

constructive dismissal and/or that it had no knowledge of the purported actions of its

officer that was alleged by the Claimant to have impinged upon him.

The Issue:

Though it is obvious so to state, the factual matrix of this case marks it as one under

the sphere of “constructive dismissal” in the realms of Industrial jurisprudence. The

issue, hence, to be deliberated is two-fold: -

i) was there a dismissal in fact and in law?

(and, if i) above is found to be in the affirmative)

ii) was the dismissal with just cause or excuse?

7

To answer this two-fold question we will first delve into a contemplation of the

established jurisprudence in this type of Industrial Court case.

The Law:

When dealing with a reference under section 20 of the Industrial Relations Act, 1967

the first thing that the Industrial Court has to consider is the question of whether

there was, in fact, a dismissal. If this question is answered in the affirmative, it must

only then go on to consider if the said dismissal was with or without just cause or

excuse. Reference is drawn to the case of WONG CHEE HONG v. CATHAY

ORGANISATION (M) Sdn. Bhd. [1988] 1 CLJ 45; [1988] 1 CLJ (Rep) 298 (Supreme

Court), as per the then Lord President Salleh Abas.

In COLGATE PALMOLIVE Sdn. Bhd. v. YAP KOK FOONG [1998] 2 ILR 965

(Award No. 368 of 1998) it was held as follows: -

“In a section 20 reference, a workman’s complaint consists of two elements: firstly,

that he has been dismissed, and secondly that such dismissal was without just cause or

excuse. It is upon these two elements being established that the workman can claim

his relief, to wit, an order for reinstatement, which may be granted or not at the

discretion of the Industrial Court. As to the first element, industrial jurisprudence as

developed in the course of industrial adjudication readily recognizes that any act

which has the effect of bringing the employment contract to an end is a ‘dismissal’

within the meaning of section 20. The terminology used and the means resorted to by

an employer are of little significance; thus, contractual terminations, constructive

8

dismissals, non-renewals of contract, forced resignations, retrenchments and

retirements are all species of the same genus, which is ‘dismissal’.” [emphasis

added]

The Jurisprudence on Constructive Dismissal:

In the case of RAVI CHANTHRAN S SITHAMBARAM v. PELITA AKADEMI Sdn.

Bhd. [2007] 1 ILR 475 (Award No. 130 of 2007) this Court held @ 483 that: -

“Constructive dismissal is a creation of the law, a fiction, where a workman ceases

employment on his own volition as a result of the conduct of his employer and

thereupon claims that he has been dismissed. As with all legal fictions it is subject to

strict requirements being proved for it to sustain itself as a dismissal de facto and de

jure and not convert into a (voluntary) resignation where those prerequisites are

wanting.”

The principle underlying the concept of ‘constructive dismissal’, a doctrine that has

been firmly established in our industrial jurisprudence, was expressed by Salleh

Abas LP in the case of WONG CHEE HONG v. CATHAY ORGANISATION (M)

Sdn. Bhd. (supra) in the following manner: -

“The common law has always recognized the right of an employee to terminate his

contract and therefore to consider himself as discharged from further obligations if the

employer is guilty of such a breach as affects the foundation of the contract, or if the

employer has evinced an intention not to be bound by it any longer.”

9

In WESTERN EXACAVATING Ltd. v. SHARP [1978] 1 QB 761 (The Court of

Appeal, England) that judicial-luminary Lord Denning adroitly elucidated this doctrine

as follows:

“If the employer is guilty of conduct which is a significant breach going to the root of

the contract, or which shows that the employer no longer intends to be bound by one

or more of the essential terms of the contract, then the employee is entitled to treat

himself as discharged from any further performance. If he does so, then the employee

terminates the contract by reason of the employer’s conduct. He is constructively

dismissed. The employee is entitled in those circumstances to leave at the instant

without giving any notice at all or, alternatively, he may give notice and say he is

leaving at the end of the notice. But the conduct must in either case be sufficiently

serious to entitle him to leave at once. Moreover, he must make up his mind soon after

the conduct of which he complains; for, if he continues for any length of time without

leaving, he will lose his right to treat himself as discharged. He will be regarded as

having elected to affirm the (varied) contract.”

In ANWAR bin ADDUL RAHIM v. BAYER (M) Sdn. Bhd. [1998] 2 CLJ 197 His

Lordship Mahadev Shanker J. decreed as follows: -

“It has been repeatedly held by our courts that the proper approach in deciding

whether constructive dismissal has taken place is not to ask oneself whether the

employer’s conduct was unfair or unreasonable (the unreasonableness test) but

whether ‘the conduct of the employer was such that the employer was guilty of a

breach going to the root of the contract or whether he has evinced an intention no

10

longer to be bound by the contract’ ” [emphasis added]. [See also HOLIDAY

INN, KUCHING v. ELIZABETH LEE CHAI SIOK [1992] 1 CLJ 141; WONG

CHEE HONG v. CATHAY ORGANISATION (M) Sdn. Bhd. (supra) and

KONTENA NASIONAL Bhd. v. HASHIM ABD RAZAK [2000] 8 CLJ 274].

And in; LEONG SHIN HYUN v. REKAPACIFIC Bhd. & Ors. [2001] 2 CLJ 288 the

High Court referred with approval to the principle stated in the case of LEWIS v.

MOTORWORLD GARAGES Ltd. (C.A.) [1986] ICR 157 which was as follows:

“It is now well established that the repudiatory conduct may consist of a series of acts

or incidents, some of them perhaps quite trivial, which cumulatively amount to a

repudiatory breach of the implied term of the contract of employment, that the

employer will not without reasonable and proper cause conduct himself in a manner

calculated or likely to destroy or seriously damage the relationship of confidence and

trust between employer and employee.”

The case above must be read together with the English Employment Appeal Tribunal

case of WOODS v. WM CAR SERVICES (Peterborough) Ltd. (1981) IRLR p. 307

where it was said: -

“In cases of constructive dismissal, an employee has no remedy even if his employer

has behaved unfairly, unless it can be shown that the employer’s conduct amounts to a

fundamental breach of the contract. Experience has shown that one of the

consequences of the Court of Appeal’s decision in Western Excavating (ECC) Ltd. V.

Sharp has been that employers who wish to get rid of an employee, or alter the terms

of his employment without becoming liable either to pay unfair dismissal

11

compensation or a redundancy payment have resorted to methods of “squeezing out”

an employee. Stopping short of any major breach of the contract, such an employer

attempts to make the employee’s life so uncomfortable that he resigns or accepts the

revised terms. Such an employer, having behaved in a totally unreasonable manner,

then claims that he has not repudiated the contract and therefore the employee has no

statutory right to claim either a redundancy payment or compensation for unfair

dismissal. For this reason, the implied term that the employers will not, without

reasonable and proper cause, conduct themselves in a manner calculated or likely to

destroy or seriously damage the relationship of mutual confidence and trust is of great

importance.” [See also the case of UNITED BANK Ltd. v. AKHTAR (1989)

IRLR 507 where Knox J. held that this is an “overriding obligation” that an

employer owes to his employee].

Dr. Dunston Ayadurai in his text Industrial Relations In Malaysia: Law & Practice

3rd Edition at page 297 states: -

“A workman can seek a remedy under section 20 only if he had been dismissed. More

often than not, there is no dispute that there was an actual dismissal of the workman

by his employer. The only issue for the Industrial Court to determine is whether the

dismissal had been for just cause or excuse, the onus of proving the existence of the

same being cast upon the employer. Where, however, the workman’s claim for

reinstatement under section 20 is founded on a constructive and not an actual

dismissal, the workman is basing his claim on the repudiatory conduct of the

employer which gave him the option to treat the contract as having been terminated.

Consequently, in section 20 proceedings of this type, the onus of proving that he has

been constructively dismissed by his employer is cast on the workman.” [See also

12

the case of CHUA YEOW CHER v. TELE DYNAMIC Sdn. Bhd. [1999] 1 LNS

104 – this addition is the Court’s].

The learned author went on to say on the same page of his authoritative text: -

“To prove that he has been constructively dismissed, it will be necessary for

the workman to establish the following:

(a) that the employer had by his conduct breached the contract in

respect of one or more of the obligations, owed to the workman;

the obligations breached may be in respect of either express terms

or implied terms, or of both;

(b) that the terms which had been breached go to the foundation of the

contract; or, stated in other words, the employer had breached one

or more of the essential terms of the contract;

(c) that the workman, pursuant to and by reason of the aforesaid

breach, had left the employment of the employer; that is, that the

workman had elected to treat the contract as terminated; and

(d) that the workman left at an appropriate time soon after the breach

complained of; that is, that he did not stay on in such circumstances

as to amount to an affirmation of the contract, notwithstanding the

breach of the same by the employer.”

Once these prerequisites for constructive dismissal have been established by the

Claimant in reference to a dismissal under section 20 of the Act the Industrial Court

then moves into the next limb of inquiry; and that is to determine whether the

employer had just cause or excuse for the dismissal. Here the burden shifts upon

13

the employer. Raus Sharif J. (as His Lordship then was) in PELANGI

ENTERPRISES Sdn. Bhd. v. OH SWEE CHOO & Anor. [2004] 6 CLJ 157 refers to

this ‘shift of the burden’; calling that upon the workman as “the first burden of proof” at

page 165 and that upon the employer as the “second burden of proof” at page 166.

And where this onus or burden of proof is upon any party in an Industrial Court case,

it is to be proved by that party to a standard of a balance of probabilities (see UNION

of CONSTRUCTION, ALLIED TRADES AND TECHNICIANS v. BRAIN [1981] IRLR

224; SMITH v. CITY of GLASGOW DISTRICT COUNCIL [1985] IRLR, Court of

Session; IREKA CONSTRUCTIONS BERHAD v. CHANTIRAVATHAN a/l

SUBRAMANIAM JAMES [1995] 2 ILR 11 and TELEKOM MALAYSIA KAWASAN

UTARA v. KRISHNAN KUTTY SANGUNI NAIR & Anor. [2002] 3 CLJ 314).

For further authority on the principles canvassed above see also the cases of:-

MPH BOOKSTORES Sdn. Bhd. v. LIM JIT SENG [1987] 1 ILR 585;

WIRA SECURITY SERVICES Sdn. Bhd. v. ABDUL RAZAK ABDUL LATIFF

[1996] 2 ILR 1396 (Award No. 526 of 1996);

MOO NG v. KIWI PRODUCTS Sdn. Bhd. JOHOR & Anor. [1998] 3 CLJ 475;

WELTEX KNITWEAR INDUSTRIES Sdn. Bhd. v. LAW KAR TOY & Anor.

[1998] 7 MLJ 359;

QUAH SWEE KHOON v. SIME DARBY Bhd. [2000] 2 MLJ 600;

LIFELONG STAINLESS EXHAUST (M) Sdn. Bhd. v. TAN DEE MEI [2004] 1

ILR 1037;

TENG TONG KEE v. NIKMAT JASA PILING Sdn. Bhd. [2006] 1 CLJ 1199;

and

14

FEDERAL AUTO HOLDINGS Bhd. & Anor. v. MD MAZLAN ABD HALIM

[2010] 1 ILR 358 (Award No: 39 of 2010).

The Evidence:

The Claimant’s Case:

It was the Claimant’s evidence that he had enjoyed a very good working relationship

with his colleagues, both senior and junior to him, ever since he had joined the

Company. That was until the emergence of an e-mail dated 6.4.2004 [see CLB 2,

pages 1 to 6] from an unknown source which was electronically circulated within the

Company casting critical accusations and grave aspersions against one Kwok Hoe

Wen [a Company’s witness at the trial designated ‘COW 3’]. This person happened to be

the Claimant’s immediate superior. It was the Claimant’s stated belief that this COW

3 was convinced that the e-mail emanated from him (the Claimant) though

categorically denied and despite the Company’s failure in its investigation to

ascertain the true source. Ever since that date it was the Claimant’s contention that

COW 3 had been picking on him with ever increasing uncouth aggressiveness and

foul-mouthed speech. This state of affairs directed at the Claimant was said to be but

the norm by COW 3 at “Daily Briefing Sessions” from 7.4.2004, onwards. To add

insult to injury it was alleged that COW 3 had instigated the Claimant’s peers to

deride him with verbal-grilling on issues outside his spectrum of duties and control at

the said daily sessions. Further, COW 3 supposedly began to assign other duties to

the Claimant’s subordinates and moved them about without the courtesy of

conferring with the Claimant; thus causing unnecessary distress and embarrassment

to him. In the midst of this ‘grinding-down’ at the hands of COW 3, the Claimant had

15

sought the advice of COW 2 (one Chim Weng Tuck – a General Manager at the Company

& the superior to COW 3). According to the Claimant, all COW 2 had to impart was for

him (the Claimant) to settle his differences with COW 3.

This build-up of antagonistic action by COW 3 culminated, it was stated, at a special

meeting where a purported new organization chart [CLB 2, page 9] was presented by

COW 3. In it, it showed that the Claimant had been assigned new duties as “Section

Manager – Board Repair & Spare Centralize”. In effect, it purported to be a transfer.

[Note: When this meeting actually took place was unclear in the evidence, but the

allegation came with an e-mail dated 1.8.2004 [CLB 2, page 10 & 11] purportedly sent by

COW 3 to the Claimant, entitled “Change of Work Role”. It would therefore not be

implausible to take it that the meeting took place at or about that period of time]. Without

going into too much detail the Claimant was livid by this turn of events. He

contended that such a transfer was unjust and unwarranted given his qualifications,

experience and years of service; and was a job that a mere “store-keeper” could do.

It ostensibly put an end to his career progression with the Company and seemed to

clearly indicate that it was engineered to end his employment/service. Presuming

that he had thus been badly and unconscionably treated, and of the considered view

that the Company was in fundamental breach of his contract of employment by this

purported transfer, the Claimant issued his letter of constructive dismissal dated

2.8.2004 [CLB 1, pages 9 & 10] and walked out of his employment, never to return,

with effect from 3.8.2004. As an aside, the Claimant stated in testimony that he had

gone along to see someone at the H.R. Department regarding this issue prior to his

letter of 2.8.2004, but no one of consequence [i.e. Omar Hakim bin Omar Farouk (COW

1) – the ‘Group H.R. Manager’, nor one Francis Xavier, an officer of the Department

concerned] were present at their offices to redress his plight.

16

The Company’s Perspective:

It was the Company’s stand; through Omar Hakim bin Omar Farouk (COW 1) – the

Company’s ‘Group H.R. Manager’ - that they (the Company) were totally unaware of

the Claimant’s troubles with COW 3; and this despite the Company having an

internal grievance procedure to deal with such like complaints. This witness

produced a document marked ‘CO 1’ which purported to be a sample-form

concerning the Company’s “Grievance Procedure”. It was stated that the Claimant

had at no time during the relevant period lodged a formal complaint in any form or

manner to the H.R. Department, either with regard to the treatment the Claimant was

allegedly suffering at the hands of COW 3; nor with regard to his opposition to the

purported transfer that the Claimant was said to have been subjected to. This

witness testified that transfers within the Company could not be done at the whims

and fancies of just anybody and such actions, and indeed any organization charts

that purport to represent any such changes in the organization must carry the

authorizing signatures of the Company’s General Manager and of the H.R.

Department to be an official and binding document. It was pointed out that CLB 2,

pages 9, 10 & 11, ostensibly issued by COW 3 to the Claimant regarding the transfer

concerned, did not carry any such endorsements. The proposition here was that the

“transfer” was merely an early stage proposal sans official approval and/or

endorsement by the Company.

Soon after the receipt of the letter from the Claimant dated 2.8.2004 claiming

constructive dismissal, this witness contacted the Claimant with a view to attempt

redress of any wrong (real or conceived) that may have been perceived by the

17

Claimant in his situation. The response from the Claimant was negative to the extent

that he appeared to reject out-right any possible alleviation of his problems at the

Company [see the e-mails exchanged between the Claimant and COW 1 found at COB 2,

page 3].

COW 2 (General Manager – Chim Weng Tuck) testified that he was unaware of the

Claimant’s bad relationship with COW 3 until he had read the Claimant’s letter of

2.8.2004, claiming constructive dismissal. He couldn’t remember about the Claimant

complaining to him about COW 3. He was also not aware of the new organization

chart [CLB 2, page 9] until the issue of the Claimant’s constructive dismissal was

raised; but conceded that the issue (regarding the transfer) could have been in the

planning stage. In any case, he had not at that stage approved or endorsed such an

organization chart (and the transfer).

COW 3 (Kwok Hoe Wen – the then Department Manager & Claimant’s superior)

testified that he did not have any issues of grievance with or against the Claimant.

He averred that he had a normal working relationship with him. He stated that the

Claimant performance at work was “good competent [sic], but there was always

room for further improvement”. He denied having uttered four-letters words to the

Claimant but admitted that he may have been critical of “sloppy work”. As regards

the transfer of the Claimant, it was this witness’s evidence that he had recommended

the Claimant for the position of head of the “Repair Board Centre” as he thought the

Claimant to be a capable worker who could get the job done. At the time in question

the “Centre” had yet to be set-up and was only “an idea which the management of

Carsem had to approve”. During his cross-examination he steadfastly denied any

18

horrible behavior against the Claimant, including but not limited to using abusive

language or meddling with the Claimant’s subordinates without consulting him.

The Evaluation:

In cases of constructive dismissal the initial burden of proof falls on the Claimant to

show the factum of dismissal. It is trite that the standard for such proof upon the

Claimant is ‘on a balance of probabilities’. With that in mind the Court will reflect

upon the allegations that the Claimant relied on to support his claim and ascertain if

the Claimant has succeeded in discharging this burden of proof.

It was the Claimant’s view that COW 3 had behaved in a perverse and

unconscionable manner first by his unreasonable conduct towards him after the

aberrant e-mail of 6.4.2004, and culminating in the purported transfer. The Claimant

equated the actions of COW 3 as being that of the Company’s.

I will deal first with the purported behavior ascribed to COW 3. Here we have a

situation of diametrically opposite versions of what in reality transpired – the

Claimant’s assertions; against the averments of COW 3; juxtaposed with the

Company’s denial of any knowledge of the same. Based on the incidence of proof –

i.e. he who asserts must prove [see also the House of Lords case of RHESA SHIPPING

Co. SA v. EDMUNDS AND Anor. (The Popi M) [1985] 2 All E R 712] – it would appear

that the Claimant has fallen far short of what was required of him. Merely asserting

the state of affairs and expecting the Court to accept the same without more is

perhaps imprudent. Furthermore, there was a grievance procedure open to the

Claimant that had he chosen to take up would have lent some credence to his

19

utterances in Court. That he was unaware of such grievance procedure and

therefore did not avail himself of it, as he implied in testimony, sounded hollow given

his position and years of service in the Company. Interestingly, CLW 2 [one Khor Aik

Chooi, a former employee of the Company called as a witness for the Claimant] seemed

aware of this grievance mechanism but alleged that the Company did not take any

action even if grievances were brought up. Although plainly hearsay evidence, of

what the Company would or would not do in any given circumstance, it pointed to the

probability that whatever the result of his (the Claimant's) complaint may have

actually been at the relevant time, had he made it (the complaint), the fact of it

having been made would have gone to some extent towards shoring-up his evidence

before this Court. As it stands, he has unfortunately failed to discharge his burden on

this aspect of his allegations.

As regards the issue of his purported transfer, it appears that he may have acted

prematurely in his actions in opposing the same by considering himself as

constructively dismissed at the point in time that he did. The Company’s evidence on

this issue was not a denial, per say. It appeared that the Company was considering

such a transfer, as they indeed had a right to do under clause 7 of the Claimant’s

contract of employment [see COB 1, page 7]; but that it had not been formalized nor

endorsed by the relevant authorities of the Company at the material time. The

propriety of such a transfer if it had taken place was not properly a subject matter

before this Court; as it is the considered view of this Court that the Claimant had

acted somewhat precipitately in the circumstances; he had not in fact at the relevant

time been transferred yet. As a corollary he had only himself to blame for the

predicament that he found himself in. He had “jumped the gun”, so to speak, thus

20

excluding any consideration or deliberation by this Court on the aptness or otherwise

of the transfer itself. He had acted far too early in all the circumstances of the case.

The Ruling:

On the evidence as a whole, based on equity, good consciousness and the

substantial merits of the case it appears that the Company did not by itself commit

any conduct that can be seen to amount to a breach of a fundamental term of the

Claimant’s contract of employment. It therefore follows that the ruling of this Court is

that the Claimant has failed to establish, on a balance of probabilities, that he had

been constructively dismissed by the Company. This finding thus negates the

necessity for the Court to deliberate upon the second of the “two-fold” question in

issue in this case, as indicated earlier in this Award.

The Final Order:

As a consequence, the claim herein is hereby dismissed.

Under my hand.

HANDED DOWN AND DATED THIS 30th DAY OF JULY 2010.

(FREDRICK INDRAN X.A. NICHOLAS)CHAIRMAN

INDUSTRIAL COURT OF MALAYSIAPERAK BRANCH

AT IPOH

21